Sandy came as Weapons Leader to 37 Squadron in January 1960 after tours with 61 Squadron, Development Squadron Watton, 206 Squadron, the Staff Nav Course, and a spell at HQCC Northwood. He was newly married and their time in Aden was very happy, shaping the rest of their lives. His wife Jan was commissioned to paint the portraits of the Federal Rulers and they became particularly close friends with Sharif Hussein bin Ahmed Al-Habili, then Federal Minister of the Interior. They learnt Arabic, travelled a lot in Beihan and the other Federal States, were welcomed into the warm and hospitable Arab society, and have kept many ties with it. After leaving 37 in April 1962, Sandy took over the role of Course Commander and Instructor at 1 ANS, another enjoyable and taxing job. However, he applied for the Service Arabic Course in an idle moment and was hoicked away after 18 months, spending the next two years at the School of Oriental Languages in Durham, and the Middle East Centre for Arab Studies at Shemlan, in the Lebanon. His wish to get back to Aden was granted in November 1965 when he went as second i/c, and later OC, of 123 Signals Unit, high on the mountain above Steamer Point. Jan and his children joined him for 18 months before all families were evacuated. This was an extraordinary time, and he and his colleagues were still in Aden after the official withdrawal, but he has sworn a dreadful swear to say no more.

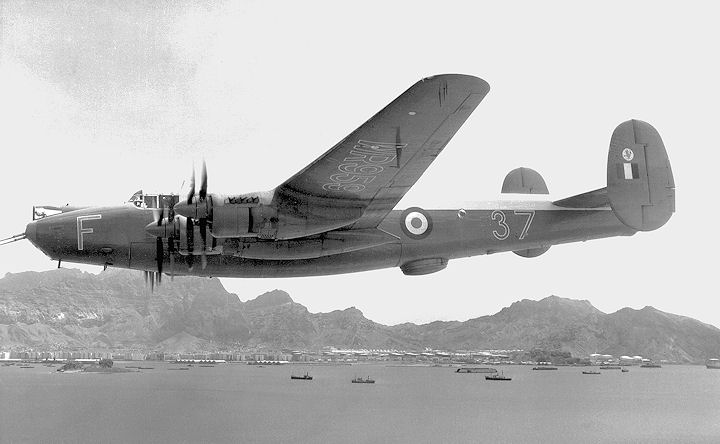

WR959-F of 37 Squadron seen over Aden Harbour from another Shackleton, WL744, during formation rehearsals which were being filmed

by the Air Ministry Film Unit on 16 March, 1962. Sqn Ldr Ken Kingshott was Captain of ’744 and Sandy was the Navigator (Sandy McMillan).

“In 2006, through a series of coincidences and serendipities, I came into contact with Stephen Day, who had been a Political Officer in Lower Yafa’ State, Western Aden Protectorate, in the 1960s. One of his responsibilities was to recommend the action that Government should take against dissident tribesmen, and in July 1961 he commissioned a Shackleton bombing mission from 37 Squadron at Khormaksar.

It’s about 0600 on Friday, 20 July, 1961, and just getting light. I park outside 37 Squadron’s HQ, a cluster of long low buildings, and go in to meet the crew for today’s sortie. Keith McDonald is my Captain, a friend and flying colleague for the past five years; we Best-Manned each other at our weddings and I’m a horribly inadequate godfather to his first child. We trained together on Lancasters at Kinloss and then served in Shackletons on 206 Squadron in Cornwall. We’re a farish cry here from jolting up and down over stormy Atlantic wastes in search of Soviet submarines or lost mariners, but at ease with each other in an enjoyable friendship and professional partnership.

Peter is the co-pilot and Rick the second navigator. Dodd the Air Electronics Officer and two of the signallers, Bas and Josh, are also about and Mike the engineer has just arrived. We’ve been crewed together for a month or so, have come to trust and respect one another’s competence and are melding into the mutually-reliant group that forms a good operational crew. Keith, Peter, Rick and I are officers and the others NCOs, but rank disappears in the air and we call one another by abbreviated roles – ‘Captain, Cap’, ‘Eng’, ‘Nav’, ‘Sig’.

A cheerful young Arab is circulating; this is Mohammed, always called ‘Chico’, who enterprisingly runs an unofficial snack bar for the squadron. He has a rusty fridge and a ramshackle table in one of the corridors, provides cold drinks and Nescafé, and makes delicious sandwiches with fresh local vegetables and rolls, and the strong cheese that’s flown in from Kenya. “Steem, Bebsi, cheese-tomato?”, he offers us. ‘Stim’ is an Aden-produced range of soft drinks; they also make Pepsi under licence, but there’s no ‘p’ in the Arabic alphabet. The squadron’s catch-phrase for ‘Excellent!’ is ‘Very cheese-tomato!’.

Our tactical function in the Aden Protectorate is ‘Colonial Air Policing’, a term betraying many underlying attitudes. This “uses operations which are psychological in intent to maintain or restore order within an area which is dissident or potentially so” (from the training manual I wrote for 37). And “It will be seen that air policing, aimed as it is at the preservation of peace, must be designed to avoid conflict, rather than seek it… all possible non-violent approaches are tried before resorting to the use of force.” Well, yes; but I’m less comfortable with this now.

South Arabia, like Gaul, is divided into three parts: the vast and barren Empty Quarter or Rub’ Al Khali where we sometimes hunt for gun-running camel trains, and which we flippantly call the GAFA (the Great Arabian F*** All); then the coastal strip that runs from Oman in the North, turns the corner at Aden on the southern tip, and extends northwest to Jordan in the Red Sea. And, sandwiched between, a great V of mountains, rainy, green and fertile in the Yemeni West, dry, barren and almost impenetrable in the Aden Protectorate East. This last is our main operational area, where we and 8 Squadron’s Hunters attempt to subdue rebellious up-country tribes people. In the Protectorate there’s no shortage of people who are ‘agin the Guv’mint’ for reasons varying from general cussedness and a tradition of arms to a preference for levying their own customs duties on passing travellers. There are also people with an honest desire for independence from what they see as colonial occupation, but we in our Hunters and Shackletons don’t know this then. We’re told that the up-country Political Advisers have identified recalcitrants who are rejecting the benefits of British advice and its civilising influence. They must be taught lessons by destroying their property while going to great lengths to avoid actually hurting or, God forbid, killing anybody.

So we drop leaflets on these allegedly frightful baddies telling them that they must be good chaps or “Government will not be responsible for its actions.” This splendid euphemism means “Come in number 7, your time is up – or we’ll huff and we’ll puff and we’ll knock your house down.” In both the Shackletons and the Hunters we have become adept at finding tiny villages, and even individual houses, in the harsh and confusing mountains and wadis of the Protectorate. We’ve also got quite good at using rockets or bombs to modify the stone and mud buildings. Not every aircraft finds the right target, and not every target is actually struck, but we mostly manage, thanks to directions from the Political Advisers on the ground.

None of us thinks to question the underlying premise, that military force will convince people to change their attitudes and actions. Nor the corollary, that if this doesn’t work first time round then an application of greater force will persuade them to say “Ah, I see that I was wrong all along.” These propositions now seem debatable.

In the Ops Room this morning, the briefer isn’t the irascible WingCo Ops (known for mysterious reasons as ‘Bubbles’), but the less abrasive Squadron Leader. He takes us through the Form Bravo that orders the operation. I start to fill in the Ops Bombing Form that details who we are, what explosive devices we’re carrying, and how they’re disposed in the bomb bay. The Met Man tells us what he thinks the weather will be: an informed guess, since there are few local reporting stations. Sand storms are an occasional hazard, but he thinks they’re unlikely today.

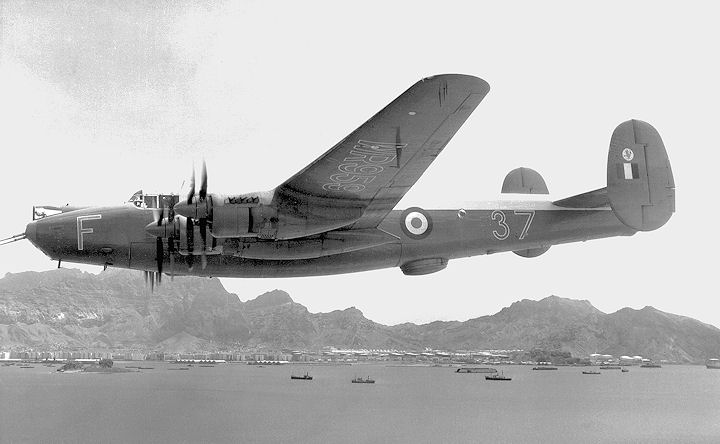

Today’s target is a village called Farar Al Ulya in the Wadi Sarar. We know it well: we were there last week and yesterday to deliver its mail, a fluttering cascade of leaflets that warned people to leave their houses lest ill befall them from the actions for which Government declines to be responsible. It’s near Al Qara, a spectacular village on a pinnacle to which we’ve also delivered leaflets and bombs. We’ve been told that it’s the home of Mohammed Aidrus, a serious dissident who needs to be taught a particularly sharp lesson.

The mountain top village of Al Qara photographed from a 37 Squadron Shackleton (Sandy McMillan).

It’s many years before I discover that Mohammed Aidrus is actually a member of the ruling family of Lower Yafa’, and one of the founders of the South Arabian League. The League is an early political and mainly peaceful movement and is almost the start of the pressure for independence that later builds so strongly. It all ends in the bloody internecine battle between NLF and FLOSY, the National Liberation Front and the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen, as British forces give up and escape; but that’s all a long way ahead of us today.

Nobody in our crew this morning knows that Mohammed Aidrus has been Deputy Ruler of Lower Yafa’ but was forced into the mountains because he refused to be docile and compliant. One man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter, in 1960s Aden as elsewhere. We also don’t appreciate that we’re about to attack Muslim property on a Friday, the holiest day of Islam’s week. For us, this morning presents a series of fairly demanding technical tasks: put a fully armed and serviceable Shackleton over a tiny village that looks very like many others, and then destroy as much as may be with fifteen thousand-pound HE bombs. Our view is apolitical, and focused on working together as a professional crew to do what we’re told as well as we possibly can – the justification of military men everywhere and everywhen.

I have many close Arab friends, so have an extra perspective which is largely ignored by my crew and squadron colleagues. I’ve contrived to compartmentalise this so that I can continue to work professionally. It will be some years before the conflict between what I believe and what I’m doing forces me to resign.

I’m first navigator, so can pull rank on Rick to oblige him to do the first transit navigation: his job is to get us within visual contact of Farar Al Ulya, not that easy in this ill-mapped and confusing terrain. I’ll be bomb aimer today for the first seven bombs of the strike, relishing some demanding technical challenges. Rick will aim the other eight bombs; I pull his leg gently with “Well, you need the practice” and he gives me two fingers. Finding Khormaksar again at the end of the sortie isn’t difficult – we just keep going southwards until the land comes to a point. We chat briefly about the route; it’s quite a short transit time, we flew it yesterday and the maps, such as they are, are already marked up, so no worries.

A Shackleton from 38 Squadron, Luqa, over the ‘harsh and confusing mountains and wadis’ of the Aden hinterland (Sandy McMillan).

Now we’re walking out to the aircraft, slightly delayed by several small annoyances – a slow fuel bowser, late delivery of the rations box, a re-check to make sure one of yesterday’s unserviceabilities has been fixed. The morning sun glitters off the sand and flashes from the windscreens of parked aircraft and passing vehicles; the day is warming fast. Ground crew and servicing vehicles cluster round our aircraft.

WR959 is a Shackleton MR II (Maritime Reconnaissance Mark 2); she’s sixteen years old and came to 37 Sqn in October last year. She’s just come back from a major service in Eastleigh (the RAF airfield in Nairobi, Kenya). Shackletons are great-granddaughter to the 1939 Manchester bomber, grand-daughter to the wartime Lancaster and daughter of the post-war Lincoln. Affectionately described as “10,000 rivets flying in close formation”, they’re primarily anti-submarine and Air Sea Rescue workhorses, with a normal endurance around eighteen hours at a stately 160 knots. The cavernous bomb-bay and pair of 20mm Hispano Suiza cannon make them ideal for 37’s colonial policing role. Shacks vibrate drummingly in the air and are noisy enough for ‘Shackleton high-tone deafness’ to be a recognised medical condition. One Army passenger was reminded irresistibly of ‘an elephant’s bottom – wrinkled and grey outside and dark and smelly inside.’

The inside of 959 is a cramped corridor of scuffed metal, sharp edges and obstructions, cluttered with equipment and projections to stab, cut or bark the unwary. Modern air travellers might find it claustrophobic. It smells of a blend of glycol, engine oil, aviation fuel, hot aluminium, worn leather and young men, with just a soupçon of Elsan fluid. But Shacks are robust and solid, their four Rolls-Royce Griffons are a great comfort, and aircrew regard them with exasperated affection, trusting them to get everybody home deafened but safe. Keith and I got used to the greater comfort and lower noise of the later Mark III aircraft on 206 Squadron, so returning to Mark IIs is a slight come-down for us.

‘… a cramped corridor of scuffed metal, sharp edges and obstructions’ (Sandy McMillan).

Keith is already walking round inspecting 959 in the pre-flight ritual of ‘kicking the tyres’ to check that we’ve got everything we should have and nothing we shouldn’t. I climb the ladder into the back of the aircraft and pass the obstacles down the long tunnel with the certainty of practice – left foot just here, side-step past Bas unloading the ration box in the galley, left hand grasps rack, vault over the main spar, duck roof projection.

I stow helmet and nav bag on the navigation table, move further forward past the engineer’s position and between the two raised pilot seats. Drop down into the nose and check the bomb aimer's panel: all bomb selector switches off, jettison bars and clips in place; clamber back to the nav’s position and check that his console is similarly safe, with his changeover switch set to ‘Bomb aimer’. Back through the aircraft, repeating the entry acrobatics in reverse, and walk under the open bomb doors to check the bomb load.

The armourers who bombed up the aircraft at first light are waiting for me. I’m Squadron Weapons Leader, so have a lot to do with these seasoned professionals. I’ve started a campaign to improve our bombing results and safety procedures, writing manuals and training people, and the groundcrew are vital to this. I’ve been encouraging bomb aimers and armourers to get together more often and share problems and solutions, so relationships and standards are improving. (I’m astonished to turn up in a New Year Honours List a couple of years later. Only a Queen’s Commendation, which is as far down as you can get without actually falling off the List, but it’s nice that people noticed what I was doing).

37 Squadron armourers bombing up a Shackleton (with local help!) (Sandy McMillan).

The Corporal Armourer and I work through the bomb bay checking that the fifteen thousand-pounders are on the allocated stations, and that they feel secure and aligned. Now I have to go back inside the aircraft again to check the camera in its floor housing aft of the door: yes, it’s aligned for vertical shots, the circuits operate, the magazine is loaded, two test exposures fire OK. We should now get high-quality photographs every time I click the switch, so I close the camera hatch. Now I must repeat the obstacle-course entry process till I’m back in the nose and can work through the checks on bomb sight and bomb-dropping mechanisms. Lights flash when they should, the distributor arm rattles over, Connell pre-selector works, the bomb release checks out on test. Everything works and the drum switch is back on ‘Safe except for jettison’.

Nearly finished: one more trip back through the aircraft and out to the armourer in the bomb bay. Together we pull the safety pins from their tail fuses, arming the bombs, and I take charge of the pins to prove we’ve done it. Fifteen thousand pounds of high explosive is now live and primed: enough to create a respectably large hole in the dispersal pan and make a number of eyes water. The corporal’s responsibility now ends, and mine begins; he wishes me luck and sets off for his well-earned cuppa char.

One final time for the obstacle race; Keith passes me as I get back to the nav station so I say formally “All safety pins out, bombing equipment and camera checked and serviceable”. “OK”, he says and makes for the left-hand pilot’s seat. I settle into my seat beside Rick, who is checking through his instruments and gear, put on my helmet and plug in the intercom. This is noisy with the familiar litany of pre-start checks as the pilots and engineer work through their lists and make us ready for today’s tasks. It’s already very hot inside 959, and everyone is stripped to shorts, desert boots and flying helmets. We’re supposed to wear our flying suits, but Authority sensibly turns a blind eye when people don’t, perhaps because heat exhaustion is not a desirable condition for operational crews. The two pilot’s windows stay open until just before take-off, as does the rear door, but it makes little difference to the increasing heat. We’re all darkly tanned, for none of us has heard of skin cancer and the aim on any overseas posting is to ‘get yer knees brown’ as soon as may be. We’re also mostly slim, another effect of the heat: I’m a stone down on my already light UK weight, and will stay that way until the end of my tour.

A navigator and (behind) an engineer ‘stripped to shorts…’ (Sandy McMillan).

Now the four Griffons are bellowing and we’re taxiing, but the delays have lost us the coolest hour at the start of the morning and put us into the danger zone for engine temperatures. Everything has got much hotter in the twenty minutes since we first got into the aircraft. Ahead of me Mike the engineer raises his left arm to check something on his panel, and I see water running like a tap off the point of his elbow. There’s a squadron competition for hottest Shack on the ground, currently held by another crew at more than 125°F. On the taxiway we’re parallel to the runway but pointing downwind, so the engines are breathing their own exhausts and Keith, Peter and Mike are anxiously monitoring cylinder head temperatures. Be forced to wait too long while others take off ahead of us, and we could start to melt Rolls-Royce’s finest products. Luckily, there’s only one Aden Airways DC3 in front and he’s away quickly, so we’re unimpeded.

As we approach the end of the runway Keith seeks to save time and cool down people and machines. He tells Peter he doesn’t want to pause to line up and hold at the end of the runway while we wait for clearance. “Khormaksar, 959 requests rolling take-off”, Peter says, and the tower comes back “959 clear for rolling take-off.” Bas slams and locks the rear door. We turn off the perimeter track onto the runway, Keith lines her up, and opens the throttles full, punching everybody hard with the acceleration that always exhilarates me. “959 rolling”, Peter says, the tower responds “959, roger” and all our 10,000 rivets thunder down runway 08 Left and climb out eastwards over the sea.

Immediately, the temperature inside drops mercifully as draughts blow through the leaky old aircraft; suddenly, it’s bearable. Wheels are up and flaps in, power is back to normal climb, and we’re turning port. “Heading please, Nav”, says Keith, and Rick responds “018, Captain”; we straighten out on course and start climbing to the 8,000 feet above sea level that we’ll need as our safety height for bombing. The target area is about sixty miles away, so our transit time is less than half an hour; I unplug my intercom, grin at Rick, pick up a marked route map and go forward into the nose.

We’re over the sands of the coastal plain; Sheikh Othman and the road to Lahej are on our left and we’re just inland with the beach and coastal track on our right. I plug in my intercom again and relax: nothing to do for a bit except keep an eye on the terrain and be ready to help Rick if we start drifting off track. After five minutes or so the coast has curved away from us to the east and I can see the cotton plantations of the Abyan delta and the villages down it to Zingibar. Jan and I were there not long ago with Sharif Hussein and a big party of retainers after an exhilaratingly hairy drive at speed along the beach. Ahead is the abrupt division between sand and the foothills of the mountains that rise up steeply across our track; as we pass over the join we level out at operational altitude.

Most of our intercom speech is curt and businesslike, with quite long silences, but today Rick says “18 minutes to target, Captain.” Then,

“Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges –

Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!”

A baffled engineer says “Do what?”; I cut in with, “Don’t you like Kipling?”; Peter says “He wouldn’t know – he’s never Kippled” which prompts Bas into, “Ah, the old jokes are the best.” “Enough, enough,” warns Keith, and we fall silent.

A little later I spot a village we know and say “Nav, I’ve got Sarar on the port side, a bit too close. We’re about two miles port of track.” “Roger”, responds Rick, goes quiet while he calculates, then “New heading 030, Captain”; “030”, confirms Keith and the Shackleton turns.

We track over the mountains and steep wadis for a little longer; we’re so close that I can switch on the bombsight and make ready to run in. There’s always a friendly contest between Keith and me to be first to spot the target, and today he wins with “Target is visual – lining up.” Now I’m about to start directing us, so I say “Bombaimer, first run for target photographs and wind finding. Nav, stand by with WFA (Wind Finding Attachment, a device that calculates local wind direction and speed from an accurately timed circuit). Captain, stand by for timed WFA run.” Both acknowledge and I start sighting for the run.

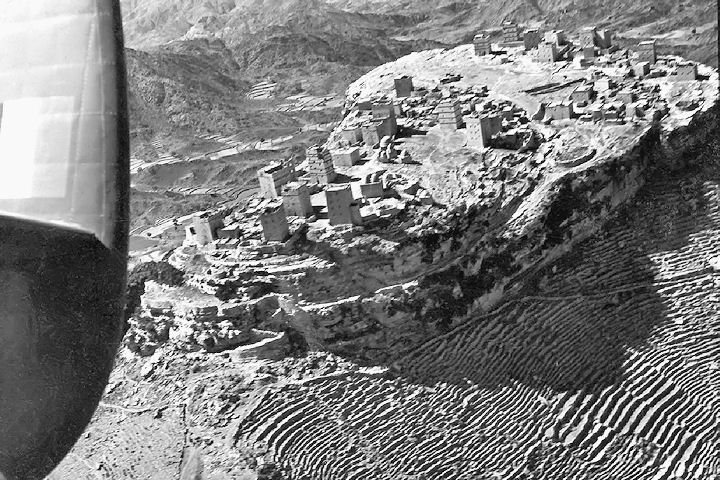

Farar Al Ulya is a typical mountain village of about twenty mud and stone houses crammed close together and perched on a mountain ridge – stray too far from your back door and you’d fall a couple of hundred feet. People build defensively hereabouts and much prefer to look down on anyone approaching. It’s also easier to shoot downhill than up, so such villages are hard to invest from below; it didn’t occur to the founders that somebody might be able to command even greater height. The ground falls away steeply into the wadis below and the slopes have been laboriously terraced into long narrow fields a few yards wide for the villagers’ crops. It’s around 150 feet long by 50 wide, about one-sixth of a football pitch, so not an entirely easy target from 4,000 feet above. A few yards undershoot or overshoot, or a few yards left or right, and the bomb will explode deep in the wadis under the village; it’s much easier to miss than to hit.

.jpg)

The village of Farar Al Ulya in Lower Yafa’, Aden Protectorate, from 4,000 feet (Sandy McMillan).

There’s nobody to be seen in the village, for they’ve responded to yesterday’s leaflets by climbing up to the nearest mountain tops for a grandstand view of our efforts. They don’t seem to have bothered to take their weapons today, for there are none of the little sparkles of muzzle-flash that we often see. Aircraft occasionally come back with neat little holes from ancient Martini-Henry rifles. One startled navigator did find a spent round embedded in his seat cushion, having narrowly avoided emasculation. Wg Cdr Bubbles sometimes threatens us with rumours that the tribes have acquired Egyptian anti-aircraft weapons, but we’ve met nothing larger than .303 calibre so far.

On one of the mountain tops is Stephen Day, the Political Officer for Lower Yafa’, who commissioned today’s strike. We don’t know that he’s watching with interest while we deliver his message to the unruly tribesmen, and it’s more than forty years before he and I are in touch.

There’s little danger in our operations, other than the normal hazards of flying with things that go bang. Though several Hunters sadly went down with their pilots, no Shackleton was ever lost in the Aden Protectorate. Keith, flying with Alan, another bomb aimer, came close one day. The aircraft had an unsuspected electrical fault in the bomb bay electrics. Turning in for their first run over a mountain peak close to the target, Alan called “Bomb doors open.” As the doors parted the fault kicked in and fifteen thousand-pounders jettisoned in a single salvo. Freed of the weight, the aircraft leapt crazily and seconds later there was the flash of a huge explosion that threw it around the sky. The safety height for thousand-pounders was 2790 feet, and fifteen had gone off on the peak a few hundred feet below, peppering the aircraft with stones and shrapnel. It was a quiet and thoughtful crew that returned to Khormaksar. As luck would have it, we heard later that the unintended jettison caused a landslide that engulfed a hostile camel train. “It’s an ill wind that blows nobody any landslides,” observed Alan.

Today, the houses have started to slide under the graticule of the bomb sight and I now have effective control; “Left-left, left-left…steady,” I say, firing the camera for some ‘Before’ shots, and Keith steers to respond. “Steady… steady… right… steady…steady…. On top… Now!”. Back at the nav station Rick starts the WFA and his stop watch and Keith takes us into an accurate left-hand circuit. I can shut up and let him expertly get on with it so I wait for the target to swing into view again some four minutes later, then talk us on until I can again say “On top, now!”. Rick stops the WFA and stopwatch and starts calculating the wind velocity over the target while Keith takes us into a wider orbit to stay in visual contact.

I’m propped face down on my elbows on the worn leather of the thinly-padded floor. The Mark 14A bombsight in front of me looks forward through the V-shaped Perspex sighting panel, and the banks of switches and bomb control gear are on my right. The vital bit of the bombsight is the collimator head (looking rather like a modern xenon overhead desk lamp) which projects a sighting cross of yellow light (the graticule) down onto a gyro-stabilised reflector glass. The aircraft’s airspeed, altitude, and nose up/nose down attitude go into the sight automatically. The bomb aimer adds the target height (to give the distance the bombs will fall), the aerodynamic characteristics of the bombs and the wind speed and direction over the target (hence the WFA fiddle of a moment ago). Now the fore-and-aft line of the graticule should track in the same direction as the aircraft is travelling, and its cross-line should show exactly where a bomb will strike. None of this will be right unless the groundcrew Instrument Fitter levelled the sight accurately at the last service, so we depend on his skill.

“Co-ordination between the members of the Bombing Team – Pilot, Navigator, Bomb aimer, and Instrument Section – must be of a high standard” says my manual, adding “Personal idiosyncracies count highly in bombing teams”. Keith, Rick, the 37 Squadron groundcrew and I are good at this; on the actual bomb run Keith and I are attuned. He knows how fast to turn when I say “Left-left…………..steady”, moderating to a tiny alteration for “Left-left steady”; we depend on his ability to hold a heavy aircraft straight and level for minutes while the turbulence buffets us. We trust one another, and our results are good and improving. Some crews never quite manage to reach this pitch: the bomb aimer doesn’t quite have the judgement, ‘the eye’, the pilot struggles to keep the Shackleton stable and responsive, the navigator’s winds aren’t entirely… But we do all right.

Bombs theoretically obey a complicated formula with lots of variables, but apparently behave rather oddly to the eye. They seem to fall straight down below the aircraft for most of their drop, but then look as if they’re racing ahead as they get near the ground. If I lean forward I can see some of this happening, but the bombsight is in the way and mustn’t be nudged or jarred even slightly or we’ll go home as failures. It’s hard to call the strike accurately so one of the signallers often goes back to the tail cone to observe results.

Rick gives me the local wind velocity from the WFA circuit and I set it on the sight. “Stand by for live run,” I say and hear Keith acknowledge with “Roger, live run, turning on.” Down in the galley helpful Josh says “Want a tail observer, bomb aimer?” “Yes please,” I say and a moment or so later Josh says “Tail cone, intercom,” as he checks in. He has crawled into a tail cone entirely of clear Perspex and this can give a sudden unnerving shock of having ‘no visible means of support.’ For a second or two one feels suspended in space and vertigo has given many of us a queasy shudder – but it’s a superb viewpoint.

Keith has taken us some way out so as to give plenty of time for adjustments and we’re now swinging onto an attack heading, the jagged mountains sliding under me in the turn. He can see the target ahead, though shortly it will go out of his sight under the nose, so he calls “Running in”; “Running in,” I acknowledge, and “Target sighted, bomb doors open”. I hear the whining growl as the doors start to part, and the draught past me increases. I flick the selector switch for the bomb on station 1, front right of the bomb bay. We’re dropping singly today; a stick of four or five might increase our chances of getting at least one thousand-pounder onto the hilltop but the village is so narrow that any line error would waste all of them.

I watch the little group of brown houses start to slide in under the graticule. We’re pretty well aligned already, though the aircraft is bouncing a bit; “Steady… steady… Right steady,” to get a tiny starboard correction, “Steady…”. The bomb release is sweaty in my hand and I’m concentrating hard. “Steady, steady, steady”. At the last second, just as I press the release, the aircraft judders and the target slips infuriatingly off the right-hand side of the graticule. “Number one bomb gone, bomb doors closed, switches off…probably a miss,” I say. A moment later Josh confirms from the tail cone, “Overshoot, 100 yards port; tough titty.”

We turn away for a second run, and something similar happens with the bomb from station 5 on the other side of the bay: the aircraft bumps at the last minute despite all Keith’s efforts, and this one is an undershoot and 150 yards starboard. Now our blood is up and we’re determined to get a hit. We line up early and settle into the groove; everything goes smoothly and as I press the switch I think ‘Good one!’. There’s a pause while we hold our breaths, I crane to watch the bomb racing over the ground dead in line with the village but lose sight of it before the burst. Up comes Josh from the tail cone “Cheese-tomato! Direct hit, Bomb aimer, dead lucky.” “Actually, we rely on skill,” I say, and somebody blows a raspberry on the intercom. As we go past the village on the downwind leg for another run we can see that the bomb has damaged several houses. “Reckon you posted that one through Mohammed Aidrus’s roof,” says Peter.

.jpg)

Direct hit as Farar Al Ulya endures its ‘cheese-tomato’ moment (Sandy McMillan).

(In one of those uninventable coincidences I’m chatting to my Bedu companion in an evening party some years later and we establish by chance that his house was one of those I knocked down. I needn’t be worried: he’s very amused and highly complimentary, retelling the story to everyone in the room. “Most of those pilots weren’t very good,” he said. “We’d sit on the hills and watch them missing. Lakin Saiyid Sandy… wallah, hu azim!” (But Mr Sandy, by God he was wonderful!)).

The sortie continues, with pauses to level the bombsight. As thousand-pounders leave us and fuel is burned up 959 gets steadily lighter, and her flying attitude changes. When this happens her nose goes up, though she continues to fly straight and level or as much as Shacks ever do. (They actually tend to hunt gently about a specific heading and altitude, being directionally and aerodynamically unstable). If we didn’t do anything about these attitude changes then we’d get increasing overshoot errors, and every so often we take time out for a levelling run.

The morning goes on; I get another direct hit and a couple of very near misses out of my other four bombs. Then it’s all change; Peter and Keith swap seats, Rick comes into the nose and I go back towards the nav station, pausing in the gangway to stretch muscles cramped by long concentration and an awkward posture.

I wander back to the galley for a coffee. It’s an unlikely rehearsal room, but Dodd is back here practising his trumpet. ‘Cherry Pink’ is mostly submerged in the uproar of four Griffons, so nobody can hear him and he avoids the usual complaints from neighbours in his Mess. Peter and Rick start methodically disposing of the remaining eight thousand-pounders; Rick gets one direct hit, one large undershoot which people jeer at, and a couple of honourable near misses.

When the last bomb has gone we fly one last overhead for an ‘After’ photograph. It’s plain that we’ve knocked the village about considerably and even Rick’s major undershoot has coincidentally taken out a tower that was on a nearby hill top. The near misses have also wiped out many of the terraces, so that fields, crops and their old walls have all fallen a couple of hundred feet into the wadis. The villagers will have to do much laborious work to rebuild their terracing by hand – no machine could get here, let alone work on those near-verticals. It doesn’t occur to us that this may mean people will starve unless they can find another source of food. We’re conscious of having done very efficiently what the briefing required of us and the legendary Martian would probably find us rather smug.

.jpg)

Farar Al-Ulya after modifications by Keith McDonald and colleagues (Sandy McMillan).

“Heading 190, 24 minutes to base,” I tell Peter, we turn for home and I write ‘Off task’ in the nav log. People are starting to think about lunch, and perhaps a bottle or two of Carlsberg in the mess bars. In twenty minutes we’re calling for clearance to re-join Khormaksar’s circuit, then letting down across Aden Harbour and over the ships at anchor to round out over the end of 08L and touch down with a screech of tyres. I log the time and ‘Landed’. Immediately, the Shackleton starts to heat up again and by the time we’re turning into dispersal everybody’s running with sweat and eager to shut down and get out. The marshaller lines us up on the pan and Peter locks the brakes on and opens the bomb doors; two groundcrew duck under the wings and chock the wheels.

People complete their after-flight checks, switch their equipment off and start packing away their gear into flight bags; one by one the Griffons run down; we’re pulling off our helmets into a silence that seems very loud, and clambering out of our seats; Josh has opened the back door and the ladder is in place; 959’s long corridor is full of people queuing to get out into the fresher air and the chance of a breeze, even if it’s almost as hot outside.

Somebody arrives from the photographic section and takes charge of the camera magazine for immediate processing. Later that evening Keith and I will stroll into Ops and delightedly discover that the photographs show how very successful we’ve been, but for now we can put 959 to bed and debrief our sortie. By the time we’ve stowed our gear away and told our story it’s just on two pm Aden time and the light is glaring. Keith, Rick, Peter and I could just make it to the Jungle Bar in the Mess for a couple of cold beers and we debate the temptation briefly.

And here I’ll leave us, momentarily irresolute in the sunlight, and return those 45 years. It’s a challenge for the 73-year-old to try to re-inhabit the 28-year-old and become aware of his perceptions and feelings for I’m very aware that all autobiography is a confabulation. “He’ll remember with advantages,” says Shakespeare’s Henry V, and some of these stories have been re-told many times. I know about some of the inaccuracies – ‘959’ wasn’t our call-sign, but neither Keith nor I can remember what it was. Perhaps some of the minor events didn’t happen on that day, but another. And we can’t recall whether we went for a beer. But there must be other errors I don’t know about, and other omissions that would make a difference to ‘the truth’ of this story.

If I could buy that young man a Carlsberg and sit down with him, would we have anything to say to one another? I’m much more aware of him than he ever was of me, for at his age “When I’m 73…” is unimaginable. He was an honourable young man; ignorant and unquestioning, but believing that he and his companions were doing an honest and necessary job in as humane a way as they might. His story is inevitably one of technicalities, of levelling settings, wind speeds and terminal velocities, of concentrating hard to get the best from mechanisms that were inherently inaccurate and often unreliable. It’s also one of trusting and being trusted, of a close-knit team where people respected one another’s abilities. There were many things to enjoy and it now seems to me that we had an easy and pleasant life with many friends from British and Arab communities and many diversions and pleasures. Some of those friendships still endure and I value them.”